Long before 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane gained recognition in technical and industrial circles, chemists searched for chemical bridges that could link organic compounds to inorganic materials. This pursuit heated up during the rise of advanced composites and plastics in the mid-20th century, especially as glass, ceramics, and plastics converged in manufacturing. Early generations of silane coupling agents had trouble sticking both worlds together, either lacking reactivity or stability. The identification and commercialization of silanes containing both amine and alkoxysilane groups—like 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane—addressed those gaps. Suddenly, industries found a route to push paints, adhesives, and rubbers to new levels of durability and chemical resistance. It’s hard to overstate how much this molecule simplified the process of preparing high-performance hybrid materials, reducing production bottlenecks at a time technology needed such breakthroughs.

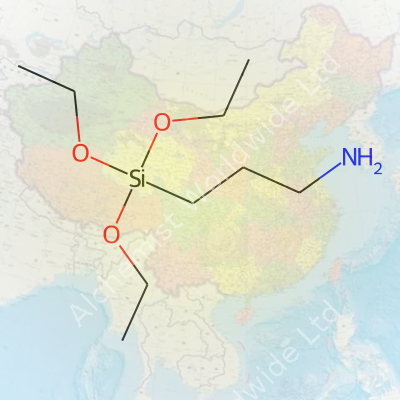

3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane, usually abbreviated as APTES, builds a molecular bridge between inorganic surfaces and organic molecules. The chemical structure tethers a primary amine group at one end to a triethoxysilane at the other. This design allows covalent bonding to glass, metals, or mineral surfaces through hydrolyzed alkoxy groups, while the amine side bonds easily with polymers, dyes, or biologically active compounds. Its wide availability makes it a go-to additive in research labs and factories. Most supply chains offer it in liquid form, packaged in amber bottles or sealed containers to guard against moisture. Shelf stability relies on proper storage, and opening a bottle means using it up before atmospheric water spoils its reactive potential.

APTES appears as a colorless to pale yellow transparent liquid, giving off an ammonia-like odor. Its molecular formula stands at C9H23NO3Si, and it tips the scale at about 221.37 grams per mole. Its boiling point sits around 217°C and it lays down a density close to 0.945 grams per cubic centimeter. What matters most in real use: pure APTES reacts quickly with water, releasing ethanol and creating silanol groups on its backbone. Left exposed to humid air, APTES can gel or polymerize, so every chemist learns to keep it tightly closed and preferably under nitrogen. The reagent dissolves in conventional solvents like alcohols and aromatic hydrocarbons, but won’t mix happily with plain water. Its electron-rich amine group gives it high reactivity for surface modifications or condensation reactions.

Every bottle of APTES should display clear labeling: batch number, purity (often at least 98%), and CAS number (919-30-2). Reputable producers specify residual water, color, and key impurity levels. These fine details matter during quality assurance, as unexpected contaminants can lower performance when modifying substrates or synthesizing advanced composites. Safety data sheets detail flash point (about 96°C), evaporation rate, and incompatibilities—especially the agent’s tendency to react violently with oxidizers or acids. Most suppliers suggest storing APTES below 25°C in sealed containers, tucked away from direct sunlight or air exposure, to preserve reactivity and reduce hazard risks.

Production of APTES begins with the reaction of 3-chloropropyltriethoxysilane and ammonia. The process runs in controlled reactors, where temperature and pressure play a role in steering yields and purity. Ammonolysis leads to replacement of the chloride with an amino group, and distillation follows to separate the APTES from residual reactants and byproducts. Manufacturers generally add stabilizers or include drying steps to ensure the final product holds up during shipping and warehousing. For smaller-scale prep—like in academic labs—the synthesis runs similarly, but extra purification steps (such as vacuum distillation) may be incorporated to suit specific research or analytical needs.

APTES most frequently shines in surface functionalization. On exposure to trace moisture, its ethoxy groups hydrolyze to form silanols, which then condense with glass, silica, or metal oxides, creating robust Si–O–Si bonds. Left on its own, the reactive amine side hooks onto a vast array of carboxylic acids, isocyanates, or activated esters, making it central in bioconjugation and cross-linking chemistry. In more advanced research, the amine is further modified—acylated, alkylated, or turned into fluorescent tags—opening up new routes in diagnostics, separation science, and nanotechnology. Few compounds rival its flexibility in surface and interface engineering.

Most catalogs list 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane as APTES, but other synonyms pop up: Triethoxy(3-aminopropyl)silane, Silane A-1100, and sometimes, 3-(Triethoxysilyl)propylamine. Some specialty suppliers mix in trade names or proprietary designations, especially for tailored grades designed for specific surface modifications. While the names vary, true products match in molecular structure and expected reactivity, so the underlying chemistry remains consistent across suppliers and brands.

Working with APTES calls for some respect. It irritates skin and eyes fast, and even inhalation of its vapors causes headaches or worse for sensitive individuals. Direct contact leaves a greasy, hard-to-wash feel—an occupational hazard in research and pilot plants. Personal experience shows simple latex gloves don’t offer enough barrier; thicker nitrile holds up better if a spill happens. Even small leaks on bench tops smell pungent and persist until wiped with plenty of ethanol. Eye protection matters, and local ventilation keeps airborne concentrations below any dangerous threshold. Standard laboratory or shop SOPs often require spill kits and neutralizing agents within easy reach.

APTES holds a place in coatings, adhesives, sealants, and emerging fields like nanomaterials or biosensors. During glass fiber production, APTES coats strands to boost compatibility with epoxy resins, cranking up mechanical strength in composites like circuit boards and aeronautical laminates. Biomedical labs value it for functionalizing glass slides, nanoparticles, and polymers, especially when preparing surfaces for DNA hybridization or protein immobilization. In electronics, fine-tuned surface modification using APTES improves dielectric performance, adhesion, and pattern transfer for microfabrication. As research moves from bulk materials to the nano or bio interface, demand for APTES only accelerates.

The future of APTES starts in the R&D lab. Scientists hunt for better, faster, and greener ways of applying it to surfaces. In my work, switching solvents and controlling humidity during deposition pushes the limits on layer uniformity—no single protocol fits every substrate, so optimization takes trial and error. Some teams combine APTES with other silanes or cross-linkers to create multi-functional coatings. As a result, hybrid materials boasting better strength, sensitivity, or biological compatibility become possible. In catalysis and drug delivery, scientists modify APTES to link metals or biologics with remarkable precision, opening doors to applications far beyond what early inventors considered.

Toxicological studies map out the dangers and limits of exposure to APTES. Tests on rats, rabbits, and fish draw clear lines: acute toxicity remains relatively low compared to industrial solvents, but chronic exposure causes skin sensitization and, at higher concentrations, organ stress. The chemical persists in aquatic environments only briefly, breaking down through hydrolysis and sunlight, though local spills still stress aquatic systems. Published safety limits—like OSHA and EU guidelines—set workplace exposure at low parts-per-million, and most industrial users operate well below these cutoffs. Ongoing research tries to pin down long-term effects for both environmental and occupational health, as widespread use means run-off and improper disposal could concentrate in unexpected places.

Innovation keeps pushing APTES into new territories. Efforts to improve water solubility, cut toxicity, and streamline application point toward next-generation derivatives, like silanes with multiple functional groups for faster, single-step reactions on intricate surfaces. Researchers focus on integrating APTES chemistry into printable electronics, flexible displays, and regenerative medical implants. Large-scale industries want more automated, less hazardous methods of application, while startups explore “green” silanes made from bio-based inputs. If demand for high-performance, customizable surfaces continues, APTES and its relatives will keep driving materials science beyond today’s frontiers.

3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane, known in labs as APTES, shows up in places most people never think to look. This compound looks like a clear liquid, has an odd smell, and usually sits in chemicals cabinets in factories, research labs, and even art studios. Many people might be surprised at how a colorless liquid with such a technical name can make such a difference across so many parts of daily life.

I remember the first time I watched a glass fiber composite fall apart because it wasn’t pre-treated. The resin and the glass just wouldn’t stick together. This is where APTES comes in. It brings the two worlds—organic and inorganic materials—closer. APTES coats glass or silica and then helps resins, like epoxy, take hold. Automotive parts, wind turbine blades, boat hulls, even sports equipment use this chemistry for tougher, long-lasting builds. Purdue University research points to silane coupling agents like APTES as key to improving the durability and moisture resistance of composites.

Poor adhesion means paint flakes, coatings peel, and expensive repairs pile up. Homeowners, artists, and manufacturers often care about how well a coating sticks to a surface. APTES forms a sticky bridge between the original surface and the paint, ink, or varnish. This bridge delivers more than just grip: it locks in vivid colors, blocks moisture, and cuts down on maintenance costs. The American Chemical Society has highlighted how the silane's amine group links to both silica and organic molecules, making it a practical choice for adhesion promoters in the coatings industry.

In the electronics world, cleanliness matters, but so does how parts connect at a tiny scale. Researchers rely on APTES to adjust the surfaces in microchips or biosensors. APTES lines up molecules so tiny wires or cells latch on in just the right way. In labs, staff prepare slides and sensors so proteins can anchor exactly where scientists need them. The surface treatment process gives microchips extra life and gives medical devices the touch of precision needed for accurate results. According to a review in Analytical Chemistry, APTES allows for controlled attachment of biomolecules on glass and silicon, driving advances in diagnostics and lab-on-a-chip tools.

Older buildings face cracks, leaks, and breakdowns—especially when exposed to water. APTES comes into play, protecting concrete and stone. Treated surfaces shed water and last longer. Compared with older water repellents, this treatment forms deeper bonds and holds up under tough conditions without changing the look of the material. City planners and architects today sometimes skip these treatments, leading to bigger maintenance budgets down the road.

Safety doesn’t take a back seat. APTES can trigger eye or skin irritation, so gloves and goggles matter on the job. Factories must keep air flowing and train workers before handling chemicals. The European Chemicals Agency recognizes APTES as a low to moderate hazard, so it ranks lower than more toxic industrial chemicals. Still, strong workplace practices keep everyone healthy. For disposal, environmental guidelines steer companies toward neutralization and careful containment, reducing risk to people and water sources.

Any time new building materials, electronics, or conservation projects show up, the question comes up: Is there a safer or greener way to get the same results? More research points toward water-based formulations and bio-based alternatives, but so far, APTES holds a solid place. It stays useful because it solves real-world problems—making things stronger, keeping surfaces clean, and even helping science move forward.

3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane works behind the scenes in many products – adhesives, coatings, and even in labs like where I once worked. I remember the surprise on a young technician’s face after a sticky mess appeared overnight inside the storage cabinet. That’s what can happen if somebody doesn’t respect how sensitive this chemical can get.

Open a bottle of 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane, and the smell leaves little doubt this stuff reacts fast. The strong, amine-like odor carries a warning: it grabs moisture from the air and starts to break down, forming messy gels and possibly even clogging up lines and equipment. Every chemist I’ve worked with agrees—tightly sealed containers matter more with this material than with many others. After each use, folks in the lab learned to wipe the rim, screw the cap on fast, and store the bottle upright, far away from routine exposure.

Most labs keep it locked in a metal or high-density polyethylene cabinet, well labeled and off the main workbench. I’ve seen careless handling ruin an entire afternoon’s work just from a few drops exposed too long. That’s a waste few can afford.

Heat speeds up all sorts of problems. We always kept 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane in a dedicated storage room, around 15 to 25°C. When a summer day pushed temperatures above 30°C, accidents became more likely. Direct sunlight also encourages faster breakdown, so shelving near windows is off limits.

For anyone in smaller setups or industry, these points don’t just keep things tidy—they protect health. The chemical stings if it gets on skin, and it’s never fun clearing up leaks because somebody took shortcuts with storage.

Some folks mix up bottles and labels, dumping chemicals into “clean” containers. That creates confusion during audits or emergencies, but with 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane, cross-contamination can ruin batches. Every responsible company stores it in the original, labeled drum or flask provided by the supplier.

When I trained new lab members, I stressed labeling and basic chemical safety. If a label peeled off, or if somebody wiped off the hazard warnings, confusion followed. Teams who treat chemical identity and date of receipt casually face higher risk—old stock of this chemical often thickens or segregates if ignored. Mark dates and use a first-in, first-out rotation for inventory control.

Ventilation shields staff from fumes. I’ve seen set-ups with proper hoods near storage, so nobody breathes in the vapors while retrieving the bottle. Protective gloves, clear safety goggles, and long sleeves become second nature after seeing a chemical splash up close. Extra absorbent pads nearby can help mop up spills fast—a lesson we learned after finding pooled liquid on a shelf.

Good habits in chemical storage make a day in the lab safer, more pleasant, and more productive. For 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane, a few minutes organizing storage and training newcomers avoid headaches that linger for weeks.

Most folks working in labs or production lines come face-to-face with chemicals that promise better materials or performance but carry their own risks. 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane finds its way into coatings, adhesives, and even the electronics industry. The upside? This chemical can boost the bond between organic and inorganic materials. The risk? Direct contact, vapor inhalation, and accidental spills can bring some real trouble for your health and your coworkers.

A clear memory sticks with me from when a coworker rushed a task and splashed this silane on her arm. Immediate redness, irritation, and a frantic run to the eyewash station capped off a short shift. The takeaway was clear: you don’t cut corners with organosilanes.

3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane can irritate skin, eyes, and the respiratory tract. Breathing in its vapors or mist may cause coughing or shortness of breath. Long-term or repeated exposure ramps up the danger, posing possible organ effects. Touching contaminated surfaces with bare hands after handling this stuff leaves traces ready to irritate the next person.

The chemical doesn’t just vanish; improper storage or disposal leads to lingering hazards in the workspace and environment.

Goggles don’t just hang around your neck. Slide them on before the bottle opens. My lab coat always picks up a few new stains each year, but chemical-resistant gloves stay clean because I change them whenever they show wear or after a spill.

Engineered ventilation matters. Working in a fume hood or with local exhaust draws fumes away from your face, not just the room. If the air feels stuffy or your eyes get itchy, that setup probably isn’t working right.

Knowing the emergency plan can save a day, maybe even a life. Spills get cleaned up quickly with absorbent pads, never with towels or rags that could spread the hazard. Colleagues watch each other for signs of exposure, calling out issues before they turn serious. Designated containers mark chemical waste, keeping the disposal process straightforward: no guessing where to toss used gloves or wiped surfaces.

Accidents drop fast when everyone takes their Chemical Hygiene Plan seriously. Spot drills and regular retraining sessions help teams handle 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane without letting their guard down. In my experience, the best labs post reminders in plain sight: glove compatibility charts, clear waste bins, step-by-step spill guides.

The more routine everyone makes these habits, the fewer late-night calls to the safety officer land on my phone. Lapses fade away when new hires watch veterans double-check labels and store bottles in cool, dry lockers away from acids and bases.

Safety grows from involvement and personal responsibility. Reading an SDS should happen before anyone cracks open a fresh container. Checking personal protective equipment for cracks or tears feels routine after a while, but skipping a day puts everyone at risk. Keeping chemicals clearly labeled and separated prevents accidental reactions, especially in a busy workspace.

I’ve seen mistakes unspool into hours of cleanup and real injuries—pain that lingers or exposures that come back to haunt weeks later. Respecting 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane keeps both people and labs running smooth. One slip can set off problems nobody wants to deal with, so diligence wins out every time.

Every few years, interest in silane coupling agents grows as manufacturers look for ways to make plastics, glass, and rubbers perform better in tough environments. 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane, often called APTES, lands near the top of the list for chemists working with these tough combinations. The structure has a central silicon atom at its core, with three –OCH2CH3 (ethoxy) groups and one propyl chain that carries an amine group (–NH2).

This isn’t a molecule that tries to hide its complexity. It has both organic and inorganic parts, so it acts as a molecular bridge. At one end, the triethoxysilane feature clings tightly to oxidized metals or glass and, on the other, the aminopropyl group connects with resins or organic molecules. This dual nature shows up in daily lab work—coating glass slides for cell adhesion or adding bite to engineering adhesives. The structural formula is usually written as (C2H5O)3Si(CH2)3NH2. Put more simply: three ethoxy arms dangle off the silicon, while a propyl chain capped with an amine group sticks out to one side.

Looking at it in two pieces makes sense. The silicon and ethoxy side loves water—exposed to humidity, those ethoxy groups quickly trade with water molecules for hydroxyl ones (–OH). On a project building biosensors, this reaction let us anchor APTES to glass, turning a slippery surface into something that holds proteins or DNA like Velcro.

Chemical structure has more to do with real-world results than most folks think. The length of the propyl chain plays a role in how flexible the resulting surface ends up. Too short, and the molecule barely reaches across the divide to bind to organic layers. Too long, and the backbone loses its strength. That final amine group shows up in active connections—when trying to link up with carboxylic acids or other reactive groups during surface treatment, it gives you a predictable site for straightforward chemistry.

The ethoxy groups aren't just decorative. In an industry setting, workers know that the rate of hydrolysis—how fast those groups swap with water—changes how evenly the final treatment coats glass or metal. Rush it, and you might end up with uneven bonding. Mix it right, and the surface holds strong, even after repeated use in harsh weather. Not all silanes give such straightforward options for surface tailoring, and this is why so many research teams keep APTES on the shelf.

Unexpected side reactions show up more often than many realize. In one lab, unchecked humidity in the room caused APTES to gel before we could even apply it. Careful control over moisture and using freshly prepared solutions helped. For large-scale applications, pre-treatment of the substrate, temperature monitoring, and solvent choice stop problems before they start. Storage matters too; old, opened bottles lose punch as moisture sneaks in and starts small, unwanted polymerizations. Keeping reagents dry—sometimes with desiccators—protects the original structure.

In the push for better sustainable surfaces, it's tempting to swap out proven molecules like this one. But the specific atom arrangement in APTES explains its wide adoption. Each part of the structure ties directly to a practical function, letting users create stable connections between vastly different materials with confidence.

3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane has turned up in plenty of university and lab storerooms over the years. Most folks recognize it as a bonding agent or a surface treatment, but it’s not the sort of chemical anyone should pour down the drain. Its silane backbone and reactive amino group mean real hazards—irritation, volatility, and reactivity with water to release alcohols. These features make its disposal a matter for respect, not shortcuts.

People sometimes overlook chemicals like these, treating them as just another bottle to move out of the way. From personal experience in academic labs, I’ve seen that mismarked or unfinished reagents easily pile up in storage. Anything with a risk label demands a process that keeps people, wildlife, and water supplies as safe as possible. Hazardous waste regulations aren’t just bureaucratic tape—research shows silane waste can harm sewage treatment systems and the downstream environment.

Raw leftovers often sit in brown glass bottles, sometimes for years. Don’t guess content or age. If the label reads 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane, treat it seriously no matter the source. For partial containers, keep the cap tight and store upright. Note any sign of container cracking or residue build-up—those signals mean it’s past the “just store it” phase.

Chemical management really starts long before disposal. Inventory tracking helps prevent unnecessary surplus. Smaller purchases and periodic audits stop bottles from gathering dust. Every chemist I know who’s ever managed a stockroom gets firsthand that fewer, fresher reagents mean safer labs and less hazardous waste in the long run.

Forget pouring, flushing, or mixing with sink cleaners. That invites regulatory fines and environmental violations. Instead, call in the campus Environmental Health and Safety (EHS) crew or trained waste management specialists. They move handled chemicals through centralized pickup schedules—containerized, labeled, and tracked right up to certified disposal or incineration.

I’ve seen reputable disposal vendors require Safety Data Sheets, waste tags, and full documentation. Facilities sometimes neutralize small traces in controlled settings, but bulk volumes need off-site destruction. For any reader working at home or outside a lab, city or county household hazardous waste programs usually offer collection events, giving the same level of containment and accountability, just at a different scale.

While waiting for pickup, keep the containers secured and separate from food, regular trash, or anything glass-clinking in your commute bag. Off-gassing or accidental breakage in a car can ruin a morning; chemical burns and hospital bills stick with you much longer.

Sharing the exact disposal pathway with lab mates or students encourages a culture where every bottle is worth a moment’s attention. Water utilities and public health agencies document persistent organosilanes like this one even at trace levels—plus the breakdown products can linger downstream. It doesn’t take much to add to that burden.

Every time a chemical like 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane leaves the shelf safely, it’s a win for the whole community. Thoughtful handling, not hasty shortcuts, keeps people—and the places we share—protected.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 3-triethoxysilylpropan-1-amine |

| Other names |

Aminopropyltriethoxysilane APTES 3-(Triethoxysilyl)propylamine Silane, 3-aminopropyltriethoxy- N-(3-Triethoxysilylpropyl)amine |

| Pronunciation | /ˈæmɪˌnoʊˌproʊpɪltraɪˌɛθɒksiˈsaɪleɪn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 919-30-2 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1362207 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:38768 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL156783 |

| ChemSpider | 71243 |

| DrugBank | DB14096 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 100.036.817 |

| EC Number | 213-048-4 |

| Gmelin Reference | 96974 |

| KEGG | C12258 |

| MeSH | D017208 |

| PubChem CID | 23816 |

| RTECS number | TP4550000 |

| UNII | F72YK6XFJF |

| UN number | UN2735 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID1020641 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C9H23NO3Si |

| Molar mass | 221.37 g/mol |

| Appearance | Colorless transparent liquid |

| Odor | Ammonia-like |

| Density | 0.946 g/mL at 25 °C |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | -0.26 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.27 hPa (20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.7 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 10.8 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -73.0e-6 cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.420 |

| Viscosity | 2.5 mPa·s (25 °C) |

| Dipole moment | 4.34 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 472.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -636.35 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -4660 kJ/mol |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS05 |

| Pictograms | GHS05,GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P280, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0 |

| Flash point | 81 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 320 °C |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 1780 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 2,990 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | VV9275000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 10 ppm |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Trimethoxy(3-aminopropyl)silane 3-Aminopropyltrimethoxysilane N-(3-Triethoxysilylpropyl)aniline 3-(Triethoxysilyl)propylamine 3-Aminopropylmethyldiethoxysilane |