Years back, chemists hunted for ways to bridge the stubborn gap between inorganic and organic worlds. By the early 1960s, industry needed something to pull together glass, metals, and plastics in ways that didn’t peel apart under stress. That’s where silane coupling agents came in. Out of that era’s firestorm of research, 3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane, also known as GPTES or KH-560, came to the market. Companies like Dow Corning and Wacker led the charge in commercializing these agents. Their goal was simple: coax composite materials into lasting marriages by offering functional groups on both ends—one for glass or metal, another for polymers.

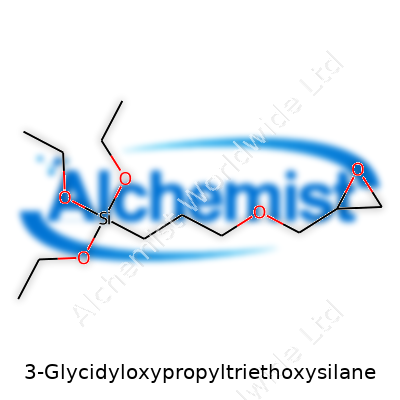

GPTES looks like a clear, colorless liquid if you pour it from the drum, and usually smells faintly chemical—nothing overpowering unless you tip your nose close. Manufacturers and researchers value it mainly for its dual-functional nature. On one side, the triethoxysilane segment reacts with glass, stone, or metal surfaces. On the other, the glycidyl (epoxy) wing opens doors for reactions with resins, paints, and coatings. This duality makes it a go-to agent in everything from printed circuit boards and composite aircraft parts to water-repelling coatings on stone and brick. GPTES never shows up in the final product with its name stamped on it, but it’s often the difference between a surface finish that flakes away and one that laughs off bad weather.

This chemical’s formula—C9H20O5Si—hints at its complexity. GPTES has a molecular weight of about 236 grams per mole, and the boiling point lands close to 290 °C under atmospheric pressure, which spells stability during most processing operations. In water or humid air, those triethoxy groups hydrolyze quite readily, transforming into silanols which then latch onto mineral surfaces. Its refractive index hovers around 1.427–1.429 at room temperature, and you can spot a viscosity near 5 centipoises at 25°C. Such numbers don’t mean much until you see how they let folks blend GPTES with solvents or spread it over a surface before it flashes off.

Packaging usually comes in steel or plastic drums lined to resist corrosion. Industrial suppliers label drums according to international standards: GPTES, CAS number 2530-83-8, and hazard designations if present. Purity should hit 98% or better for coatings and adhesives, while minor traces of water or chlorides draw attention due to their impact on shelf life and performance. Users scan for inventory codes and UN numbers tied to transport protocols: UN 1993 for flammable liquids is a frequent one, given the solvent blends used in shipping.

Manufacturers produce GPTES in a single-step approach most of the time. Their method involves epichlorohydrin reacting with 3-chloropropyltriethoxysilane in the presence of a base. Sodium hydroxide steps into the mix, encouraging the chemical ring opening needed to bolt the glycidyl group into place. The crude product goes through vacuum distillation to remove any leftover reactants and pesky secondary products. A plant blending this compound will always look out for heat build-up, since runaway exothermic reactions can create dangerous spikes during large batch synthesis.

The epoxy ring in GPTES acts as a reactive hub. Under acidic or basic conditions, it opens and forms covalent bonds with amines or other nucleophiles inside resins or coatings. This reaction secures polymer chains right onto the silane-treated substrate, locking them tight. People with experience in resin modification often graft special molecules onto GPTES’s glycidyl group or swap out alkoxy units to tailor performance for specific substrates. That tinkering doesn’t always go smoothly, but it has led to innovations in corrosion inhibitors and tougher composite resins for sporting equipment.

This compound goes by a living list of names: glycidoxypropyltriethoxysilane, gamma-glycidoxypropyltriethoxysilane, GPTMS, A-187, and Silquest® in branded contexts. Companies write purchase orders using CAS 2530-83-8 to cut through naming confusion. Each synonym crops up in different patents, research papers, or safety sheets, so keeping the alias sheet handy helps avoid mix-ups—especially in a lab where missing a prefix might mean mixing the wrong silane into a critical batch.

Working with GPTES calls for respect. Its liquid form can irritate skin and eyes, so gloves and goggles aren’t optional if you want to avoid nasty rashes or stinging burns. Spill vapor turns flammable, as with many organic solvents, and local rules demand proper ventilation in factories and labs. Companies look to material safety data sheets (SDS) before introducing GPTES into daily handling, making sure proper spill control kits and eyewash stations stay close. Storage in sealed plastic or steel containers away from humidity stretches shelf life. Regular training for handling and first-aid protocol isn’t paperwork; it washes off nasty surprises in real-world plant floors.

Plastics, paints, adhesives, and sealants draw heavy use from GPTES. In fiberglass-reinforced plastics, its value shines by creating chemical bridges from the glass fibers to the surrounding matrix, so finished parts flex and stretch without splitting at the seams. Paint chemists blend it into primers for bridges or marine hulls, helping coatings stick hard to metal and concrete while braving assault from saltwater and sunshine. Electronics companies treat circuit boards with silane finishes to fend off moisture creep and prevent costly shorts. Medical device engineers, exploring biocompatibility, experiment with GPTES-treated surfaces to help diagnostic chips bind to desired molecules.

Academic and corporate labs chase fresh uses for GPTES. In nanotech, scientists rally around this compound to attach nanoparticles to glass or metal, creating hybrid materials used in sensors or flexible displays. Researchers publish papers on the modification of the silane end groups, picking apart how to tune anti-fogging and self-cleaning glass coatings. Durability studies in architecture zero in on GPTES habitually, especially as urban developers demand coatings that hold up to acid rain or freeze-thaw cycles without surrendering. The push for environmentally friendlier variants encourages chemists to invent less toxic analogs or recyclable silane blends, looking to cut end-of-life impact.

Plenty of animal and cell studies seek answers to how dangerous GPTES could be. Short-term exposures at work sites have tied the chemical to skin and respiratory irritation. Data from rat inhalation and ingestion tests point to moderate toxicity if handled in bulk or in unventilated spaces. Long-term environmental studies suggest the chemical hydrolyzes and breaks down reasonably fast, lowering the risk of persistent pollution, but scientists still look for metabolic byproducts with potential for chronic health effects. Regulatory agencies monitor workplace exposure and flag improper handling, justifying the continued work on robust safety training and alternatives that work just as well.

As industries keep searching for stronger, lighter, and more resilient materials, demand for coupling agents like GPTES will surge. Trends in electric vehicles, wind turbines, and green construction spark new applications requiring tailored surface adhesion and moisture resistance. Research teams reach for GPTES while developing flexible electronics, advanced batteries, and even recycled composites. Simultaneously, calls for green chemistry inspire chemical engineers to minimize environmental hazards throughout the GPTES life cycle, making manufacturing cleaner and end products safer for people and planet. The story of GPTES doesn’t end here; as long as material science keeps pushing boundaries, so will the styling and forms it takes on shop floors and in research journals.

Many people never hear about 3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane unless they run across it in a lab or industrial setting. The name itself sounds like it belongs in a technical manual buried on a shelf. But this chemical has quietly shaped modern materials we use every day, adding strength, flexibility, and durability in ways most folks don’t realize.

Working in automotive and construction years ago, I watched as engineers searched for ways to get fiberglass and resin to stay bonded without peeling or breaking down. They needed something tough enough to survive sun, rain, and years of vibration from engines. That’s where 3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane comes in. This compound acts as a coupling agent. On one end, it latches onto glass, metal, or stone. On the other, it grabs onto plastic, rubber, or resin. Think of it as a handshake between two very different worlds—mineral and polymer.

Without this handshake, composites often fall apart under stress. Imagine using a glue that will only stick to certain surfaces. Without the right chemistry, materials used in things like wind turbine blades, car panels, or even plumbing fixtures could snap or leak long before they’re supposed to.

I’ve painted more fences and fixed enough leaks to know that coatings and adhesives matter more than most people think. Manufacturers mix in 3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane to toughen up paints, sealants, and glues. With it, coatings won’t peel off metal gates after a winter of freezing rain, and adhesives stay strong even as temperatures swing. This chemical lets paint cling better to surfaces. It keeps waterproof sealants from shrinking or cracking.

Anyone who opens up a computer or home appliance will see circuit boards dotted with tiny, delicate chips. Today’s circuits pack so many wires and transistors that moisture, heat, or just time can fry the whole thing. The ingredient list for the coatings and encapsulants covering these boards often includes 3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane. Adding this molecule, manufacturers give their electronics a fighting chance against water damage, static, and decay.

Like any strong chemical, 3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane brings risks, especially if inhaled or spilled on the skin. Workers in industries handling this compound wear gloves, goggles, and use proper ventilation to avoid problems. Research shows it can irritate skin or eyes. Some tests flag it for potential longer-term effects with repeated exposure. Governments regulate its handling to keep risks low, but workers and managers stay alert.

Some industries research safer substitutes, exploring bio-based silanes or new bonding agents with lower health risks. Others tweak processes, using digital tracking to measure doses, or switching to closed systems to limit fumes. Sharing best practices and investing in staff training make a difference. As green chemistry grows, labs and manufacturers hunt for options that offer strong bonds without dangerous side effects.

I’ve seen firsthand how one ingredient changes the way products last or fail. 3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane doesn’t get headlines, but the bridges it forms—between glass and plastic, or between durability and convenience—show how unseen chemistry supports roads, wind farms, and old pickup trucks. Balancing innovation, safety, and responsible use will shape its future, just as its quietly shaped what we rely on every day.

3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane sounds like quite a handful, but anyone who’s worked in a lab or on an industrial floor recognizes it by its more common role as a silane coupling agent. I’ve worked with so many substances, but this one always sticks in my mind for its sneaky way of breaking down if you don’t give it some attention. This compound features reactive groups that love to go through hydrolysis or unwanted reactions if the environment tempts them just a little. Water vapor in the storage area, or even a leaky cap, will nudge things in the wrong direction, leading to clumps or changes in viscosity. Nobody wants to reach for a drum and realize it’s turned into useless goo.

Lab veterans know you can’t treat this silane like table salt or even like simple alcohol-based chemicals. Keeping it dry goes beyond just screwing on the cap. You need a dry, cool spot, and several layers of defense. I’ve seen what happens if you leave a bottle uncapped during a busy shift—it takes in moisture fast, and you get condensation once you bring it back to cooler temperatures. That’s a recipe for waste and a surprise mess the next day. A desiccator or dry cabinet provides an ideal space, with a regular check on those silica gel packs inside giving peace of mind.

This silane compound prefers temperatures on the lower end of room temperature. Warm conditions speed up unwanted reactions, even if you keep things dry. My team once stored materials in a warehouse that rose above 30°C in the summer. Not only did some labels peel off due to sweat and moisture, but the contents inside our silane bottles changed color and smelled different. Sticking to something close to 15-25°C kept product loss to a minimum, and an insulated storage cabinet for higher purity grades made a big difference.

The fumes released from compounds like this one are more than just unpleasant—they can lead to headaches, and nobody wants repeated exposure in a closed space. I always recommend using a vented cabinet or ensuring that storerooms stay well-aired. Any container must seal tightly, ideally with a screw- or clamp-type lid, to block air and water. Investing in sturdy storage isn’t about being fancy—it reduces leaks and saved us from at least one call to the chemical spill response line.

No one gets excited about inventory logs, but they’ve saved my department more than once from accidentally opening too many containers at once. Marking down the date you first opened a bottle, and keeping older stock up front, helps use up silane before age degrades its value. Watching for the slightest yellowing or cloudiness gives a quick heads-up that something’s gone off. Good records turn into good savings, even when it feels like paperwork overload.

This isn’t a compound you want to buy in bulk just because the price seems right. Short shelf life and sensitivity to air and moisture require careful purchasing and prompt usage. It’s better to order smaller amounts regularly, so supplies always stay fresh. I’ve seen operations save money and frustration after following this simple rule.

Summary: Give 3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane the care it asks for—keep it dry, cool, sealed, and well-labeled. Your team, budget, and finished results will thank you.

3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane pops up in a range of industries. Manufacturers use it as a bonding agent in coatings, adhesives, sealants, and sometimes composite materials. You might not notice its name on common products, but it's part of a group of chemicals that help make materials more durable and resistant to environmental stress.

People in industry encounter this chemical as a liquid, usually clear or slightly yellow. Just because it looks harmless doesn’t mean you can get relaxed about handling it. I’ve seen safety data sheets that treat it with respect, warning about skin irritation and eye damage. Those who have mixed or applied it with bare skin often regret skipping gloves. Prolonged or repeated exposure leads to redness or even allergic reactions. Breathing in heavy vapors irritates the nose and throat.

OSHA and other agencies set clear guidelines for chemicals like this. For a good reason—overexposure in a poorly ventilated workspace leaves employees open to headaches, respiratory trouble, and worse. Anyone working with epoxies or silanes knows the scent of “chemical-smell” that lingers on skin and clothes. Employers should keep the material contained, insist on gloves and goggles, and treat spills with urgency.

Not every chemical shows up on the top-ten hit list for cancer, but ignoring the research is a gamble. 3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane contains an epoxide group, which means it has the potential for reactivity in the body. Some epoxides are tied to long-term health effects, including possible carcinogenicity. Although current studies don’t show a red-flag cancer risk at typical exposure levels, there isn’t enough quality data for a clean bill of health. Cumulative exposure through accidental skin contact or inhalation raises questions that only time and good research will answer.

Laboratory tests consistently flag the need for caution. Rats and mice react to high doses with liver and kidney damage, but those levels exceed what most humans would see in a controlled workplace. Still, seeing these effects in animals suggests a need for vigilance, especially as workplace protections sometimes lapse.

Splashing chemicals down the drain or letting them leak into the soil brings new headaches. These silane-based products can hydrolyze in water and produce smaller molecules, some of which stick around longer than you’d expect. Bad disposal practices endanger water systems and the health of people living nearby. I’ve seen small towns grappling with mysterious “burning nose” odors and breathing trouble, later traced back to mishandling of industrial chemicals. Here, the importance of following environmental rules becomes crystal-clear.

Most problems come down to education and equipment. Proper storage, labeled containers, and regular use of personal protective gear all help reduce risk. People in charge must stay up to date with research, using trusted sources like toxicology updates, OSHA regulations, and peer-reviewed studies. Regular air monitoring catches leaks and airborne contamination before symptoms develop among workers.

Anyone using 3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane can push for better workplace habits—don’t skip reading the safety data sheet or insist on quick shortcuts to save time. Health and safety rules matter most when the effects of exposure aren’t easy to spot until years down the line. Choices made now protect people for decades to come.

Anyone working with specialty chemicals knows that watching out for shelf life isn’t just about following a label. 3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane, commonly called GOPS or GLYMO, plays a pivotal role in everything from adhesives to glass coatings. Once a batch hits your loading dock, the clock starts ticking. Ignore shelf life, and you invite headaches like poor bonding, failed performance, or even health issues. That’s not an exaggeration—in the lab or on the shop floor, old chemicals can turn a simple task into an unexpected risk.

Most suppliers stamp a shelf life of around 12 to 24 months on GOPS, assuming the drum remains sealed and stored at room temperature. Manufacturers set this based on actual stability testing, not marketing guesswork. Open that drum too soon or leave it out in a steamy warehouse, and shelf life shrinks fast. Heat, humidity, and contact with air all invite hydrolysis, kicking off a series of reactions that produce byproducts and degrade its performance.

GOPS reacts with moisture in the air. Even undetectable seepage through a partly closed lid can trigger trouble. Ethoxy groups break off, water sneaks in, and the chemical starts to gel or turn cloudy. In my own experience, a cloudy GOPS solution leads to weak bonds, especially when working with glass fibers or specialty coatings. It might look fine to the naked eye for weeks, but the drop in performance shows up down the road—sometimes when a whole batch of painted glass fails quality checks. There’s no shortcut around the science, and no quick fix once the chemistry heads in the wrong direction.

Checking for shelf life doesn’t stop at reading a date on the label. Labs use straightforward checks: visual inspection, viscosity measurement, and even simple water solubility tests. One quick tip from the trenches: if GOPS looks hazy or thicker than it used to, don’t gamble with it. Storing it below 25°C in its original packaging, somewhere dry, and tightly closed keeps things alive for the long haul. Decanting into small, airtight containers also shields the bulk from too much exposure.

Plenty of us want to avoid chemical waste, but using expired GOPS is a bad idea. Some try to stretch life with drying agents or filtration, but that’s rarely worth the risk. Relying on out-of-spec chemicals can cost more down the line—think recalls, warranty claims, and lost customer trust. For businesses, tracking each lot’s receipt date and regularly auditing inventory gives a clear path to safe and predictable handling. I’ve seen facilities benefit from simple spreadsheets and barcode systems. This helps avoid surprises when deadlines loom.

Getting the most from GOPS means respecting its limits. Reliable shelf life isn’t just a matter of rules on a datasheet. It ties back to real results—bonds holding up, coatings clinging for years, jobs done right the first time. Accepting this upfront saves headaches, protects workers, and ensures products stay strong all the way to the end user. Nobody wants to bet their business or their safety on expired chemistry.

Painters, car makers, and electronic engineers often face challenges in adhesion. Cracked paint on walls, delaminating adhesives in smartphones, and moisture damage in circuit boards all trace back to poor bonding between organic and inorganic surfaces. 3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane, or GPTMS, is a mouthful, but it plays a practical role behind the scenes. Drop a few grams of this silane into a resin or coating, and you can see how much easier it grabs onto tough surfaces like glass or metal.

In the lab, investigating new paints or epoxies, I’ve noticed results take a leap after adding GPTMS. Its special structure — with the epoxide group on one end and ethoxy silane groups on the other — lets it grip both sides. Imagine trying to glue a plastic badge onto a steel desk. Standard glue barely holds for a day, but with GPTMS as a bridge, you’ll need real force to pull it off.

Roughening a surface physically can help, but surface chemistry finishes the job. GPTMS creates a strong chemical bond between glass, metal, and the resin, giving more lasting results than simple sanding or priming. Construction adhesives, wind turbine blades, and even computer chips use it for this reason. The news stories about glass-epoxy composites snapping under stress — that’s exactly the gap GPTMS helps to close. Nobody wants to see solar panels blowing apart in a storm, and every extra bit of bonding resilience pays off over years in the field.

Water resistance also deserves mention. GPTMS reacts with moisture in the environment to form robust siloxane bonds, which prevents delamination or peeling from humidity. In my experience with outdoor epoxy applications, those without proper silane treatment often failed within months, especially when exposed to a rainy climate.

GPTMS gets added during the mixing process, usually alongside a hardener. You don’t need large amounts; even a single percent by weight often makes a difference. For everyday users, the key involves stirring thoroughly and making sure the surface to be bonded has been cleaned and dried. Any dust, oil, or moisture will cut into performance. Some folks chase after the newest and most expensive adhesives, but proper surface prep with GPTMS in a common epoxy brings more improvement than many realize.

Electronics manufacturers dip microchips and printed circuit boards into GPTMS-toughened encapsulants to block moisture and keep circuits intact over years of heating and cooling. In high-performance car shops, mechanics use it to ensure resins stick to metal panels and don’t rattle loose during races. Even if most people never see or buy GPTMS directly, the reliability of finished goods owes a lot to this one additive.

Too many products still end up in landfills due to weak adhesion or lack of weather resistance. By taking a page from advanced chemical surface treatment and applying GPTMS more widely, companies can deliver longer-lasting products and avoid costly recalls or replacements. In the end, a small tweak in a formula makes a world of difference for anyone tired of failing glues or flaking paints. There’s real value in taking advantage of simple tools that add durability and reliability, both for businesses and for customers who count on stuff to just work.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 3-[2,3-Epoxypropoxy]propyltriethoxysilane |

| Other names |

GPTES GLYMO Epoxypropyltriethoxysilane 3-(2,3-Epoxypropoxy)propyltriethoxysilane 3-(Triethoxysilyl)propyl glycidyl ether |

| Pronunciation | /ˌɡlaɪˌsɪd.ɪˌlɒk.siˌproʊ.pɪl.triˌɛθ.ɒk.siˈsaɪ.leɪn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 2602-34-8 |

| Beilstein Reference | 84261 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:60043 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1943683 |

| ChemSpider | 16038 |

| DrugBank | DB11286 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03c53a7c-fa86-42b0-9d68-6880f4a29915 |

| EC Number | 216-846-4 |

| Gmelin Reference | 1252067 |

| KEGG | C19600 |

| MeSH | D017209 |

| PubChem CID | 8712 |

| RTECS number | VV8400000 |

| UNII | N8E8TS24UV |

| UN number | UN2810 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID5032516 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C12H26O5Si |

| Molar mass | 278.38 g/mol |

| Appearance | Colorless transparent liquid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.07 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | 2.1 |

| Vapor pressure | <0.01 hPa (20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 14.5 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 1.6 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | −6.1×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.427 |

| Viscosity | 10 cP at 25°C |

| Dipole moment | 2.20 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 573.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1096.7 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | Not assigned |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | `GHS07,GHS05` |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H315, H317, H319 |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P264, P271, P272, P280, P302+P352, P305+P351+P338, P321, P362+P364, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 210 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 8025 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) of 3-Glycidyloxypropyltriethoxysilane: "7.8 ml/kg (oral, rat) |

| PEL (Permissible) | No PEL established. |

| REL (Recommended) | 50 ppm |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

2-(3,4-Epoxycyclohexyl)ethyltrimethoxysilane 3-Glycidyloxypropyltrimethoxysilane 3-Glycidyloxypropylmethylsiloxane 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane 3-Methacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane |